Last week in English, we spent quite a bit of time dissecting the first paragraph of Charles Dickens’s “A Tale of Two Cities.” You know, that run-on sentence, “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times, [insert 239857230573 more opposites]”?

(An aside note, you would not believe the amount of…well, implausible stuff – and that’s the PG-rated version of what I really want to say – Honors kids will come up with. There were so many pretentious ‘interpretations’ being thrown around I honestly wanted to hit myself – or someone – with a brick for most of that week.)

Anyhow, obviously, one point of analysis that got brought up a lot was this idea of all this repetition of hope/despair, light/darkness (or I should say, Light/Darkness), heaven/ambiguous ‘opposite way’, spring/winter, etc. and these opposite extremes tied in with the ‘two cities;’ essentially that either (1) the two cities alluded to in the title would be one being all the good things (hope, Light, heaven, etc.) while the other would represent the bad ones (despair, Darkness, etc.), or (2) that the whole idea of this book would revolve around two extremes, that there would be no middle ground.

(“In the game of thrones, you win or you die. There is no middle ground.” Okay, I’m sorry, I’m done. Ignore this; just me geeking out. Game of Thrones, come back to me.)

No offense or anything, but I call BS to this whole ‘no middle ground’ stuff.

Is this world in 2D or something? Are we all flat, like on a piece of paper? No. We are all multi-dimensional, multi-faceted people. Our world is multi-dimensional and multi-faceted. Same with stories. In fact, even more so, because stories can contain multiple people; multiple worlds. The idea that such a book would revolve around this idea that there’s only one or the other with no middle ground is, frankly, implausible, and pretty much impossible, if you actually think about the logistics of writing a book.

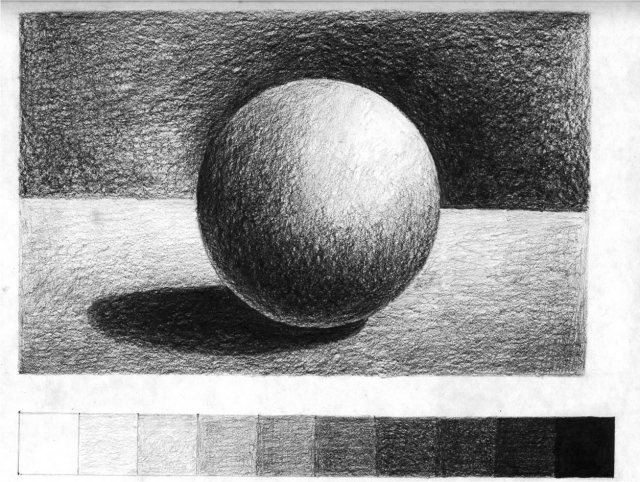

Listen, as a writer who knows a lot of other writers, one thing I can say for certain is that no book is worth reading if it only talks about one extreme and its opposite. A good story, or character or plot for that matter, is something that’s multifaceted; painted in shades of gray rather than just stark black and white. Much as a drawing or painting falls flat without shading and depth, a story falls flat without a ‘middle ground’ between two extremes. (Humans are finite; and with that means that no one is 100% anything. No one is 100% good or 100% evil, and if you think so, it just goes to show how little you really know.)

For those of you in AP European History, think back to when we were studying Renaissance art, and, if possible, a little earlier to the Middle Ages. Remember all those 14th century paintings of the saints with the same long-necked, long-faced, thin-eyed waifs everywhere? Remember how flat and boring those were? And then, BAM! Renaissance art. Colorful, realistic, deep – and why? Because these Renaissance artists used depth and perception. Because they used chiaroscuro – (like the fancy art term? because it’s probably the only one you’ll get in a while; I know about (this) much about art) – which is ‘the treatment of light and shade in drawing and painting.’

Light and shade. Not light or shade. Not light on just this area and only shade in the other. Light and shade, blended together to give more sides, more depth and meaning.

Just as a painting needs a balance of light and shading, a story needs that same balance of two extremes. ‘Shades of gray,’ so to speak, are necessary to make a story realistic and give it more meaning – quite literally, this balance, this happy medium between Dickens’s ‘Light’ and ‘Darkness’ is the difference between a stick figure and Mona Lisa.

18th century or 21st, nothing is in black and white.